Our short lives on earth make it easy to think the natural world is nice and stable. We cycle through the seasons. Maybe a few storms sweep through. Otherwise, left to its own devices, earth is a steady thing. Right?

Not quite. The world—its climate included—is always shifting and changing. The earth wobbles on its axis, receiving more sunlight or less. The amount of carbon in the air naturally fluctuates, causing warmer and cooler periods.

Credit: Hans Grobe / Creative Commons

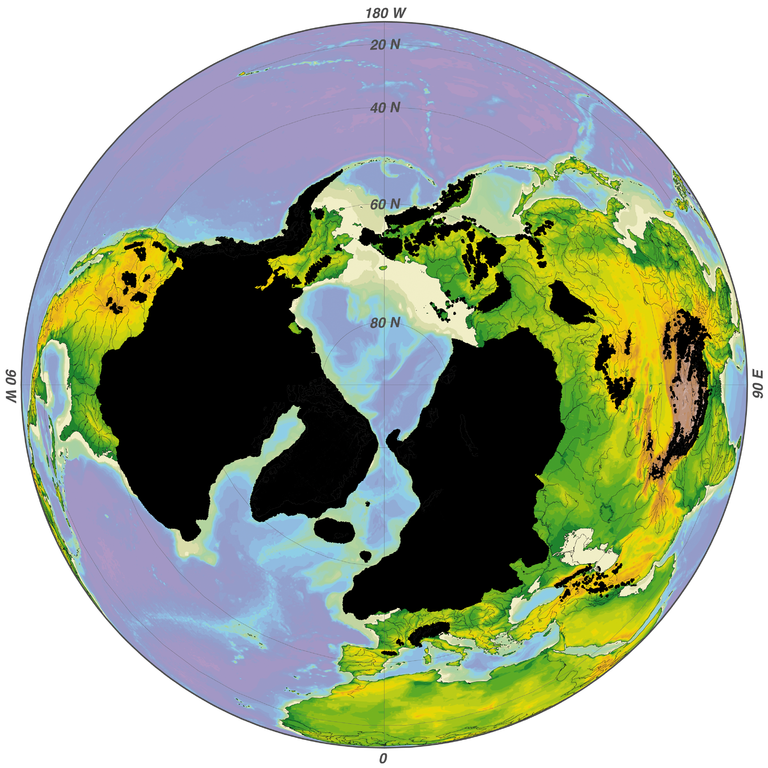

Last Glacial Maximum

This was the apex of the last ice age, so, of course, the world was much cooler, probably between 3 and 5 degrees colderthan today. Glacial ice sheets reached down from the Arctic, extending as far south as Germany in Europe and New York City in North America. (And much further south, many mountains were capped with glaciers, too.) But a slight shift in the tilt of the earth's axis meant that more sunlight began to reach the poles. The world slowly began to warm, causing glaciers to retreat.

Credit: Steinsplitter / Creative Commons

Younger Dryas

After an extended period of increasing temperatures, the climate cooled slightly. It stayed cool for roughly a thousand years. (The name of the period comes from the white dryas, an Arctic wildflower that, found buried in ancient sediment, has helped us understand past climatic conditions.)

Scientists believe the Younger Dryas may have been launched by shifts in ocean currents. In some places, the drop in temperature was large—as much as 14°C. On other parts of the globe, though, temperature increased. These sorts of complex changes are typical; indeed, after the Younger Dryas it becomes difficult to generalize about global climate change.

The Holocene Begins

Glacial activity in the Sierra Nevada helped scientists identify the period of Neoglaciation. Credit: F Cary Snyder on Unsplash

Neoglaciation

After an extended warm period, the climate cooled and glaciers began to advance again. The Neoglacial period lasted roughly a thousand years, though its precise borders are hard to define, in part because there were still substantial regional oscillations in temperature and precipitation.

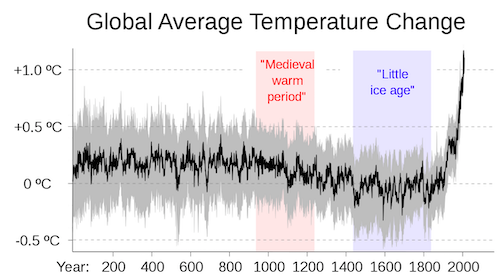

Medieval Warm Period

Credit: RCraig09 / Creative Commons

Little Ice Age

After that nice period of warmth, the planet cools again. (Note that the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age overlap: that, again, is because the climate's behavior has varied from place to place.)

The existence of both the Medieval Warm Period and the subsequent Little Ice Age has sparked controversy, in part because a naturally warmer era has been cited as evidence that current climate change might not be human caused. There is one difference between these events and the current warming, though: they tended to be scattered, happening in different times in different places, rather than the globally synchronized increase in temperature we're seeing today.

"Global Cooling"

Over a few decades in the twentieth centuries, global temperatures declined again. Some scientists actually worried about a crisis precisely opposite from today: that the world may cool to a dangerous extent.

Today, this temperature dip is attributed to solid and liquid particles called aerosols, which humans had been releasing for centuries. Aerosols reflect some sunlight away from earth, thereby dampening temperatures. This is a quick and short-term effect, whereas the greenhouse effect of carbon is slow-moving and long-lasting, and had not yet caught up.

Breaking Records

Credit: USGS

The Eruption of Mount Pinatubo

Credit: Oregon State University

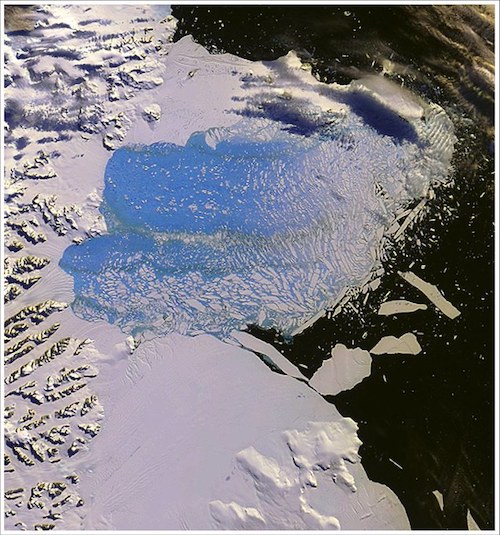

The Breakup of the Larsen B Ice Sheet

After a series of warm summers, 3,250 square kilometers of an Antarctic ice sheet disintegrated in a quick 35-day collapse. It was the largest such collapse ever observed, setting off a wave of news coverage.

Heat Wave

Credit: NASA

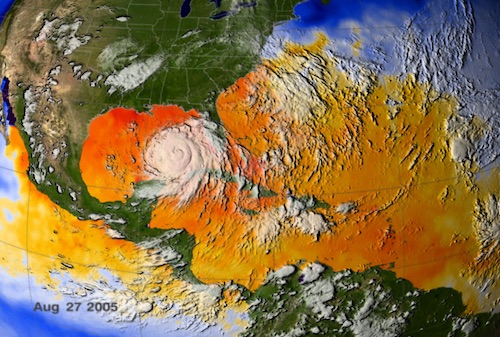

The Hurricanes

New Borders

Credit: Matt Howard / Unsplash

More Bad News

What Comes Next?

A new decade begins with a global pandemic. Not that there is any relief from climate-induced catastrophes: record-breaking wildfires flare in the U.S. West and Australia and the Arctic. The hurricane season is so active that the World Meteorological Association runs out of names. (They have to turn to Greek letters instead.)

What will come next? That's in part up to how we respond to the cataclysms we are dealing with right now.