Scientists recently announced a grim fact: 2020 matched the hottest year ever recorded, equaling the record-setting temperatures of 2016. There's not much reason to expect this record to last long. Before 2016, the 2014 had been declared the hottest-year ever; before that, 2010 earned the same superlative.

It's an unfortunate truth: The world is hotter now. But what about heat waves—those long, miserable periods of extended heat? Unsurprisingly, you can expert more of these, too. Here's what the science says.

What is a heat wave?

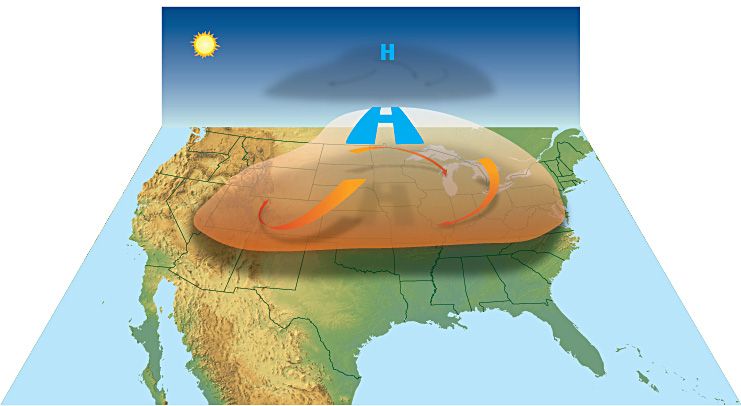

Heat waves are generally caused by high pressure building up in the middle layers of the atmosphere—3,000 to 7,500 meters up. This pressure causes air to sink downwards, which prevents heat on the surface from rising, as it typically would. The lack of flow also inhibits the formation of clouds and rain, which would also dispel heat.

Just what qualifies as a heat wave is difficult to define. Temperatures vary from place to place, so what one person considers onerous heat might feel normal elsewhere. Temperatures have changed throughout time, too, so it's difficult to set a baseline for what the temperature "should" be. It's important to note that the studies I cite below employ different definitions, though generally they all come down to extended periods where the temperature stays above some chosen threshold.

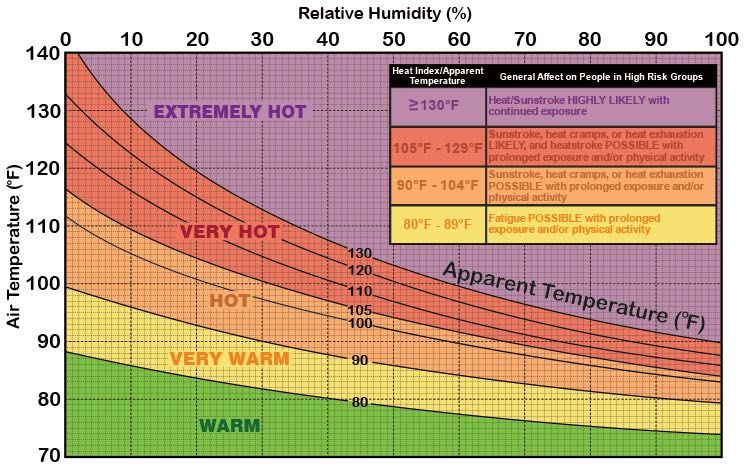

Given the way our bodies regulate their temperature, certain combinations of heat and humidity become deadly.

There are a few specific variables it's important to consider when discussing heat waves. There are certain thresholds that, once crossed, impact human health. For example, our bodies decrease their internal temperature by sending blood towards the skin's surface, where the heat can escape out into the air. But this only works if the air is cooler than our body.

We have a second method of cooling ourselves, too: sweating. Some heat is required for sweat to evaporate; as this heat is consumed, the result is a drop in body temperature. But this only works if the sweat can evaporate. If the air grows too wet, there is no room left for moisture; that means our sweat stays liquid. That's why humid air make high temperatures feel even hotter. Meteorologists incorporate this fact into "feels like" temperatures, which give us a more complete description of the weather conditions.

What is happening to heat waves?

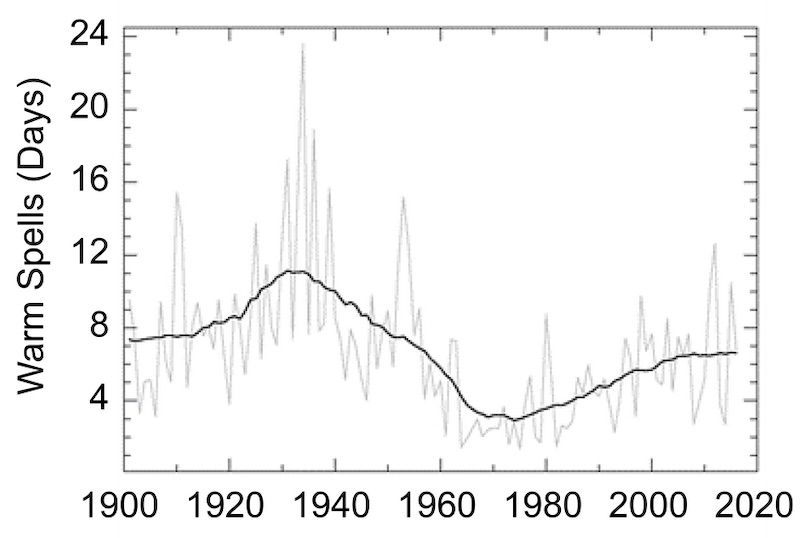

Some studies have found that there are now fewer heat waves than there once were. A 2017 report found that U.S. heat waves peaked in the 1930s, and then dropped substantially. Lately, though, heat waves have become more frequent and slightly more intense.

Thanks to climate change, this trend is likely to continue, with heat waves increasing in both the U.S. and Europe. That's not solely due to the general increase in temperature, either. The atmospheric circulation patterns that cause extended heat waves are being intensified by the warming climate.

Humans suffer most from hot air. But there are heat waves in water, too, and these are also growing worse: recently, heat waves in ocean waters have grown 34% hotter and 17% longer, which can be devastating to ecosystems. In lakes, heat waves are expected to grow as much twelve times longer by the end of the century.

Because of the hard-to-define nature of heat waves, it's difficult to put specific numbers on future conditions. One measure, though, is "person-days per year of high heat index conditions." This number counts all of the people who have to live through a high heat index day, then sums the total number of such days they'll have to endure. One study found that in the U.S., the historic numbers have been around 107 million annual person-days annually. That might jump as high as 2 billion by the end of this century.

Billions of people are likely to endure extraordinary heat in the coming years, which could drive new waves of migration.

The cities and towns we've built make this problem worse: All the pavement traps heat, which is why cities can be 4°C warmer during the hottest part of the day. As cities grow—which they're projected to do—this effect will also increase. Heat waves will likely become an issue of climate justice, too, since the hottest neighborhoods are often occupied by people of color.

What does extreme heat do?

Heat waves are a "threat multiplier," and amplify the effect of other dangers. As I noted above, the still air that accompanies heat waves prevents cloud formation and impedes precipitation—which means heat waves exacerbate both droughts and wildfires. The trapped air is also likely to hold more particulates, since there is no wind to clear away pollution.

The heat causes plenty of damage itself. Roadways can melt and buckle; crops can wither. It is harmful to humans, too, as noted above. It may surprise you to learn that heat is the deadliest form of weather hazard there is.

Intense heat can melt highways and cause wildfires—and is more deadly than any other kind of weather. The rise of heat waves is likely to drive a new era of global migration.

The U.S Center for Disease Control defines heat stress as a specific illness that results from a body's inability to cool itself; symptoms include brain damage and organ failure. In 2003, during a summer heat wave in Europe, as many as 70,000 people died.

Often, though, heat waves attract less attention than tornadoes and hurricanes. Perhaps that's because they are slow and creeping, and don't offer a dramatic visual spectacle. It may also be because people can escape into air-conditioned buildings—though this creates a feedback loop, as the electricity surge leads to more emissions, which will eventually lead to more heat waves. (All those churning A/C units can also drain the electrical grid, leading to power outages.)

And not everyone has access to air conditioning. One study found that 96% of the people killed by heat in the U.S. were non-citizens—often farm workers who were weathering miserable conditions for low pay.

By 2070, as many as 3.5 billion people may live in places where the mean average temperature is higher than 29°C. Scientists have calculated that the idea range for human beings is between 11° and 15°C. Such extreme heat, then—and its deadly consequences—is almost certain to drive massive migration, reshaping global politics. Even if you have the luxury of an air conditioner, then, this is a crisis you won't be able to ignore.

Read this next:

What does 'cap and trade' mean?

August 31, 2020 · Climate knowledge