A carbon offset is an effort to counterbalance some amount of carbon emissions. There are two ways to do so: by removing carbon dioxide that's already in the atmosphere, or by preventing future carbon emissions from ever reaching the atmosphere.

Carbon offset projects were first funded by national governments as part of an effort to meet the requirements of a global climate-change treaty. Now, though, the concept has trickled down to consumers, prompting a bewildering array of questions. Can I trust Microsoft and Amazon when they say they are offsetting their emissions? Should I pay extra money to offset my car rental? Should I offset all of my own emissions?

Over the next few weeks, in a series of posts, I'll try to answer these questions and more. To begin, we need to dive into the world of offsets.

📚 Jump to section:

What kinds of projects can offset emissions?

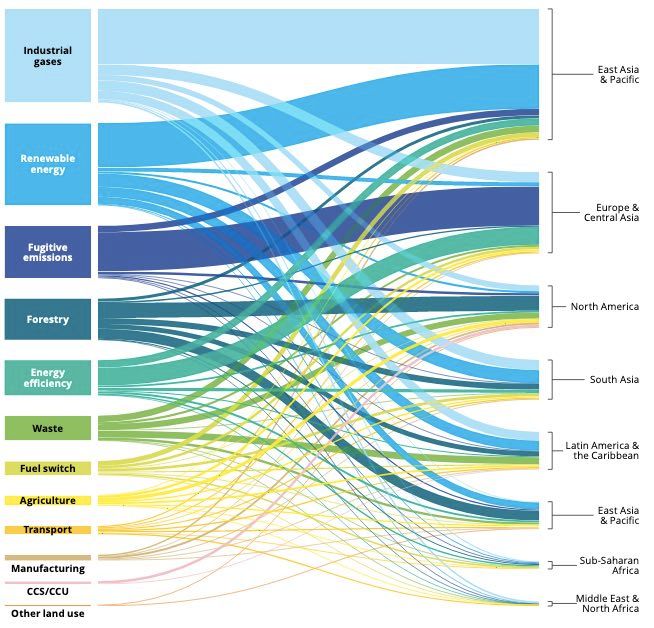

There are thousands of offset projects out there, from renewable power plants to farmers to new agricultural practices that hold more carbon in soils. The UN has noted more than 200 categories of offset projects, in fact.

In general, offsets can be divided into two overarching categories: emissions removed and emissions avoided.

To make sense of all these projects, it helps to split them into two overarching categories. First—and simplest to understand—is the act of carbon sequestration. This is also known as carbon "removal," because it literally removes carbon from the atmosphere. This is done through various mechanisms: machines can "scrub" carbon out of ambient air; certain rocks will bind with atmospheric carbon. Once the carbon has been removed, it must also be stored (or sequestered). The most permanent way to store carbon is to inject the carbon into underground rock. To get all this done, though, is very expensive—as much as $1,000 per tonne.

Trees also pull carbon out of the atmosphere as they grow; the carbon is converted into cellular materials, and thus is stored inside its trunk. So reforestation, too, can be a viable sequestration strategy—though it can be difficult to ensure the carbon stays in the tree.

Forestry has been an increasingly popular category, accounting for more than 40% of the offsets issued over the past five years, according to the World Bank. But not all forestry projects are about removing carbon. Some fall into the second overarching category of offsets: avoided emissions.

The idea here is to identify a source of future emissions and intervene to keep those emissions from ever being released. In the case of forestry, this means saving trees that are almost certainly fated to be cut down—thereby keeping their stored carbon from reaching the atmosphere. (Indeed, given the current rates of logging, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has said that preventing deforestation is a more pressing priority than planting new trees!)

Certain industrial gases (like refrigerants) have a potent greenhouse effect; unused gases sometimes just sit in tanks, slowly leaking into the atmosphere. Companies now search for such tanks and incinerate their contents as a way to avoid emissions. (According to the World Bank, industrial gases have accounted for more offsets by volume than any other industry.) Similarly, landfills produce methane, a greenhouse gas, as organic materials break down. Technology can be installed to capture this methane so that it never reaches the atmosphere. Renewable energy was once a popular offset category, too, though for reasons I'll get to next week this category is declining in popularity.

Increasing energy efficiency offers a way to avoid emissions, too. In many countries, home cooks still use inefficient stoves. Distributing better stoves—as well as cleaner-burning cooking fuels—can quicly reduce emissions. Such projects a clear "co-benefit," too: the fuel makes the local air less polluted, reducing the health impacts of kitchen smoke. (Wren supports one such project.)

Can I really trust these projects?

As an astute reader, you probably some concerns here. Amazon is paying some other company that promises to avoid emissions on their behalf? That's a relationship that seems to depend on a lot of faith.

Indeed, there have been high-profile embarrassments. In 2002, the band Coldplay wanted to offset the impact of its album A Rush of Blood to the Head, and paid to have 10,000 mango trees to be planted in India. The money never got to local landowners, and few trees survived.

Forestry projects can also burn in a fire—or the trees can be removed by loggers. This makes forestry projects, in general, somewhat high-risk as offset projects—though those risks can be managed. We support an agroforestry project in Scotland, for example, in part because the region has never experienced a wildfire.

There are other concerns to consider, too. Sometimes, forest reserves that have already been protected for decades receive payments as carbon offset projects. This is counterproductive: it means that a major company claims it has canceled out its carbon emissions, but nothing has actually changed. The trees were always going to be there.

For an offset project to do what it's supposed to, it must be "additional." That is, it only exists because of the money received as an offset.

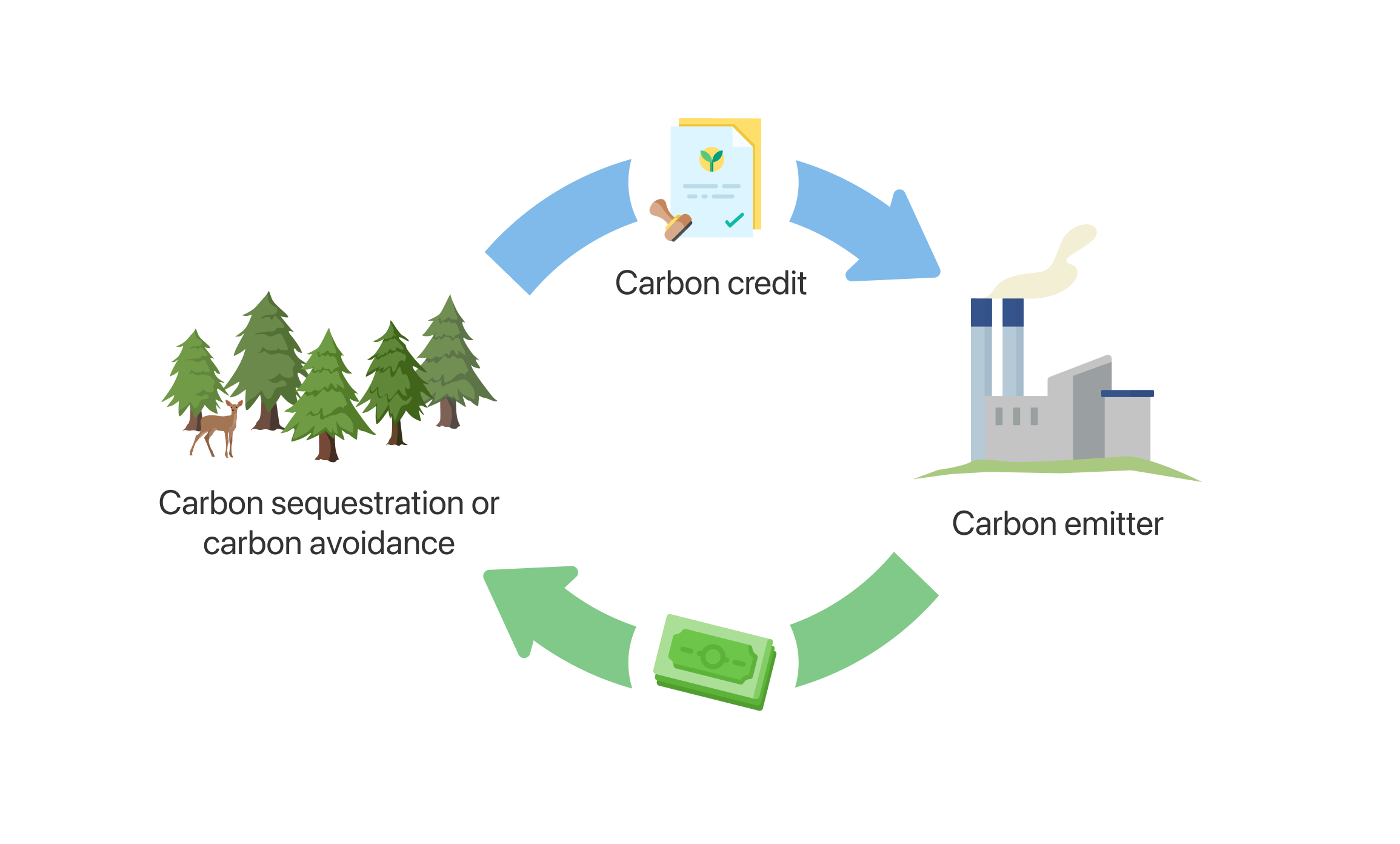

There are agencies that work to certify which carbon offset projects are worthwhile. If such an agency approves of a project, it will issue a "carbon credit"—generally in units of one tonne of CO2—that can be sold to companies like Amazon. I'll dive into such agencies later in this series; for now, understand that no one has completely solved the puzzle presented by trying to certify many, many projects in one system.

If you're wanting to gauge a company's commitment to the climate crisis, one thing to investigate is how many emissions they have managed to reduce before they turned to offsetting. This is a critical first step: offsetting should be reserved only for the emissions that are extraordinarily difficult to eliminate. In a world where so many systems have been built around fossil fuels, there are some emissions that are simply beyond the control of an individual or a single firm—and its only for these that offsets should really be used.

Carbon offsets and you

A carbon credit covers a full tonne of CO2, nearly as much as the average American emits in a month. So when you see an option to offset the emissions of your car rental, you're not buying a full carbon credit, just a small slice.

This is done through what's called an offset "retailer." These companies purchase credits, and then break them apart to distribute them across individual customers. For the consumer, this system makes for a challenge: There are a lot of layers of information to untangle, so it may be difficult to learn just how high quality the underlying offset project is. If you can find out enough to feel confident you're investing in a good project, go for it! Otherwise, though, it may better to do your own research and find a project you can support on your own initiative. (Though we are admittedly biased here, since we offer you the opportunity to do so!)

What if you want to go beyond just one car rental and offset all of your personal emissions? That is—in a way—what we offer here at Wren. We allow you to support projects that avoid emissions or remove carbon, and help you understand just how much carbon your dollars are keeping out of the atmosphere.

As a company, our default stance is to be skeptical of any individual offset project, and to seek as much information as possible.

We think it's important that you—just as much companies—seek to reduce your own footprint as far as possible before you begin offsetting. But it can be helpful, too, to think of your contributions to projects not as a substitute for emissions, but instead an attempt to do as much as you can to support a process that is essential to society. After all, even if we cut emissions completely right now, carbon removal will remain necessary to hold warming below 1.5°C.

As a company, our default stance is to be skeptical of any "offset" project. The projects we've chosen to partner with—just four at the moment—have been identified through extensive research as truly effective. You can see our rationale for each of these products on their respective pages, where we also include monthly updates where the projects report on their progress. And if you have questions or concerns, we always want to hear from you.

Read this next:

A guide to non-renewable resources and the climate

September 29, 2020 · Climate knowledge