What is nature for?

This question set off a fierce debate in the United States in the early twentieth century—even among people who all appreciated wild, empty places. Both sides agreed that nature should be protected. The question became how nature should be protected—and, really, why. "Conservationists" saw nature as a valuable resource, one that needed to be managed carefully so its value could persist. "Preservationists," on the other hand, thought nature was less an economic resource than a spiritual sanctum. Nature should be preserved simply because it is beautiful.

As a shorthand, think of the difference between a wilderness park and a national forest. The former—the domain of the preservationist—is a playground in nature, where we aim to leave no trace; the latter is the conservation's landscape, where loggers carefully cull trees and hunters pursue game.

These are simple enough definitions. But what is nature for? This, even a hundred years later, remains up for debate.

📚 Jump to section:

How did the divide emerge?

People have managed landscapes for thousands of years. Indigenous cultures use fire to clear space for favored resources and have done so for generations. (Carefully planned fires also prevent larger, more destructive wildfires.) In the late eighteenth century, a very different practice emerged in Europe: Rudimentary scientific methods were applied to forests in an attempt to increase the yield of timber, and therefore the amount of profit.

By the late 1800s, this concept had taken firm hold in Europe and even jumped across the Atlantic. It fit U.S. politics well: Engineers and scientists were often asked to solve the era's problems, from determining the most healthful foods to design effective public spaces; now they would tackle forests, too.

The U.S. Forest Service was launched in 1905, and aimed to keep public forests economically useful over the long term. This same mode of thinking applied to other resources, like rivers, which could be engineered to provide hydroelectric power and to irrigate arid land. Such was the "proper use" of nature, as people often said: to conserve it so as to ensure its long-term utility. These people became known as conservationists.

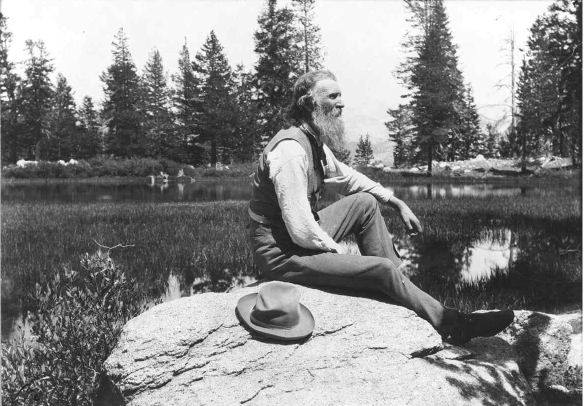

The mountaineer John Muir, though, believed nature offered a spiritual salve. ("The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness," he once wrote.) Muir and his followers declared that nature had no proper use. It had its own right to exist, and should be preserved in its perfect, untrammeled state. The people who held this viewpoint became known as preservationists. The spirit of this philosophy is reflected in the U.S. effort to establish national parks.

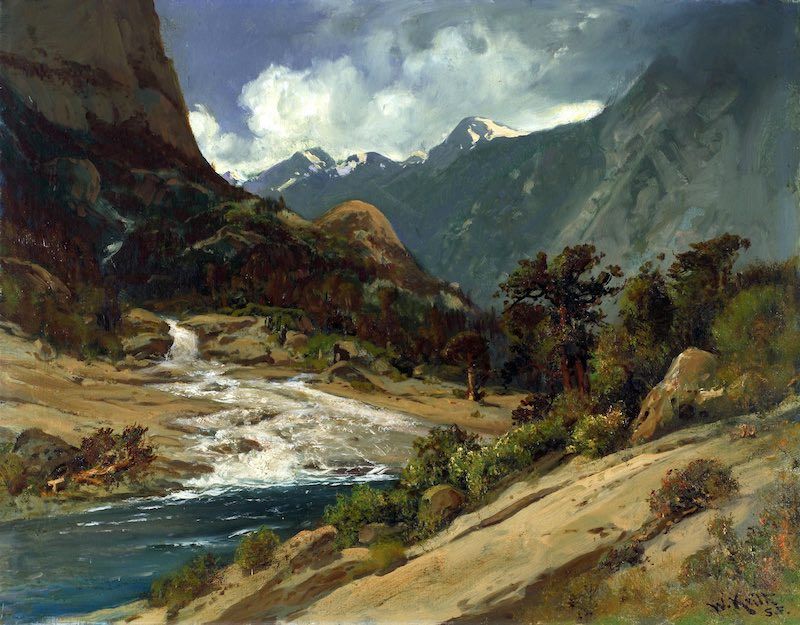

These two views came to head in the early 1900s, after the U.S. Department of the Interior granted the city of San Francisco rights to the water in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, which lay inside the recently formed Yosemite National Park. The city wanted to build a dam to store water—the exact kind of careful planning prefered by conservationists. Muir loved the landscape of the valley. He thought that it made as much sense to "dam for water-tanks the people's cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man" than Hetch Hetchy. Despite Muir's efforts, the dam was completed in 1923.

How are these words used today?

Most people today can't articulate the difference between conservation and preservation any more. Indeed, in many cases, the two words are used interchangeably. Even among specialists, the words don't have the same meaning as they did in 1923.

The terms "conservation" and "preservation" have shifted meanings through the decades, making the old debate harder to track.

Today, the word "conservation" tends to refer to the discipline of conservation science, which emerged in the 1980s and focuses on retaining the world's biodiversity. The motivations for conserving biodiversity span both sides of the old argument: Some scientists hope to use biodiversity as a resource; others simply believe all species deserve to live.

The discipline of "preservation," meanwhile, tends to focus on human culture, not nature. Preservation Magazine is published by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which works to keep historic homes and artifacts in their original state.

The idea of "nature preservation" has fallen out of favor, in part because nature does not really have an original state to preserve. John Muir's notion of empty, human-less wilderness dismissed the long presence of Indigenous people in America, people who had altered the landscape to their benefit.

So is the old controversy over?

Not at all. The Hetch Hetchy debate centered on how the U.S. should use its public lands. That remains a contentious question. Indeed, at Hetch Hetchy itself there is an ongoing campaign to remove the dam so that the preceding landscape can be restored.

A even more heated battle is unfolding in southern Utah, at the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments. The "national monument" designation is intended to preserve landscapes of historical and scientific interest, and prevents certain developmental activities. After President Trump came to office in 2017, he reduced the size of both monuments, opening some of their lands up to mining. Conservation groups working to protect endangered species and organizations focused on outdoor recreation have both sued in an attempt to restore the former protection.

Even people who can agree that the "proper use" of nature may not include uranium and coal mines still disagree about just what the word "nature" means. Within the field of conservation science, there is fierce debate over how human beings fit into the world's wider web of ecosystems. Here, too, the contours of the debate have shifted since 1923.

Human beings dominate half the land on earth. Perhaps other species deserve a bit of space, too.

That's in part because climate change has forced our hand. As the world warms, it's going to be harder and harder to sustain old ecosystems. Changing temperatures will force some species will leave their current range. If the goal is the conservation of individual species, conservationists may need to create habitat "corridors" that facilitate migration, or to intervene directly to carry species along. (Human beings will be among the species forced to move, of course; human climate migration is really already underway.) This can make the idea of "preservation" of landscapes seem all the more silly. How do you preserve something when the entire world is changing?

Still, it's not like we want to just stop protecting tracts of land. Old-growth forests are better are storing carbon than young forests—which makes their survival all the more important today.

In 2012, Peter Kareiva, the chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy, published an essay that set off a firestorm. Kareiva never used the word "preservation," but he criticized the idea of wilderness parks, places intended to be empty of people except for passing spiritual supplicants. In subsequent essays, Kareiva built a case for what became dubbed the "New Conservation," a movement focused on conserving not just pristine landscapes, but also places that have been altered by human beings. Other conservationists objected that this was in essence giving up on the many untrammeled places that still remained.

This debate, like the battle over Hetch Hetchy, has at its center a familiar specter: money. What is nature for? That question is also asking how ecosystems should fit into our economy. Kaveira suggested scientists needed to stop "scolding capitalism" and start partnering with corporations—perhaps by setting prices on the "services" provided by ecosystems. Which has subsequently happened: You can help fund conservation to offset your carbon footprint on Wren, for example! More generally, though, a Swiss insurance firm has noted that trillions of dollars are at risk due to looming ecosystem collapse. Still, the "ecosystem services" concept has been criticized, as it has a supply and demand problem: Commodities increase in value in large part because they become rare.

Other critics of Kaveira worry that capitalism, so often focused on endless growth, is part of the problem—that it can and should be scolded. After all, human beings take up nearly half the globe. If all the other species are going to get some space of their own, we may have to set ourselves some limits. No matter where you land, though, it's worth noting the point of agreement throughout all these eras: nature has value and needs our protection. The world can't survive unless we recognize that fact.

Read this next:

What does 'global warming potential' measure?

August 10, 2020 · Climate knowledge