If you've read much about climate change, it's likely you've come across a four-letter acronym: IPCC. That stands for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, an organization that was created in 1988 to provide governments with accurate and objective climate science.

The IPCC won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 for their work helping humanity understand the crisis we face. Though the agency has endured scrutiny over the years, lately its emerged as an essential voice in the fight against climate change. Here's how it works.

📚 Jump to section:

What does the IPCC do?

Officially, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change focuses on "assessing the science related to climate change." Assessing is a key word here: this organization does not conduct original research; it reviews and summarizes the science that already exists.

The main output of the IPCC is its reports. The most important of these are the "assessment reports," which take stock of recent science, indicating what we know about climate change and what we need to be looking into. These reports aim to be comprehensive: they examine causes, impacts, and potential solutions. Peer-reviewed research is prioritized, though other sources—like government reports—are also consulted. So far, the IPCC has produced five assessment reports.

The IPCC does not produce science but instead reviews the recently published research, synthesizing it into a single report.

The agency publishes other reports, too. "Special reports" focus on specific topics that have been flagged by global governments as particularly important. (The most recent special report looked at oceans and ice amid a changing climate.) "Methodology reports" provide governments with guidance on how to measure their greenhouse emissions. All of these reports go through multiple drafts, and must be approved by various experts.

How is the IPCC structured?

The IPCC includes 195 member governments, each of whom is a part of the United Nations or the World Meteorological Association (or both). An IPCC plenary meets at least once each year and includes a representative from each member government.

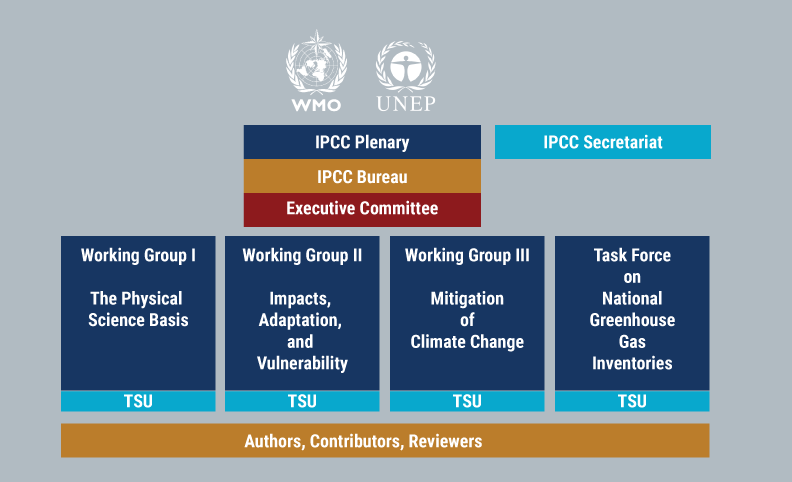

At the outset of each "assessment cycle"—the time required to produce an assessment report—the IPCC elects a new "Bureau" of chairpeople to oversee. A subset of these chairs also sit on the executive committee, which ensures the work proceeds in a timely fashion. There are also 14 full-time employees who make up the IPCC Secretariat, a support staff organization and financial manager that is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. Finally, there are three "working groups," each focusing on a major component of the report, as well as a "task force" that assesses greenhouse gas emissions around the world.

Each member government can nominate scientists to serve as contributors or reviewers for the report; the Bureau selects from among these nominees. The scientists serve as volunteers and are not paid.

What is the IPCC doing now?

Right now, the IPCC in the midst of its sixth assessment cycle. This cycle has already included the release of three special reports—one on oceans and ice, as mentioned above; another on land use; and, finally, a report focused on the ambitious 1.5°C warming target included in the Paris Agreement.

With those special reports completed, the IPCC is now focused on the sixth assessment report (which in IPCC parlance is sometimes shortened to AR6). The report is supposed to be published next year, before the first global "stocktake" occurs—an event where nations will come together to assess their progress towards the goals in the Paris Agreement.

How did the IPCC come about?

The first world climate conference was held in 1979, after members of the United Nations began to worry over a potential warming crisis. More meetings and conferences were organized by various bodies over the subsequent decade. One shortcoming, though, seemed to always repeated itself: These were scientific groups, and did not represent the world's governments in any official capacity.

The IPCC was formed in 1988 by the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization as a hybrid, where expert scientists would double as official government representatives. Often, these scientists are drawn from national laboratories or governmental scientific agencies.

Some historians believe the IPCC was intended to cripple the growing climate movement. Instead, it's helped spark real change.

The U.S. administration at the time—helmed by President Ronald Reagan—was instrumental in the creation of the agency. Given Reagan's overall resistance to environmental regulations, some historians believe he intended to cripple the nascent climate movement: yoking scientists to their governments might constrain them; requiring consensus amongst so many countries might block action, too. Instead, though, the IPCC's ability to reach consensus has served to underline the seriousness of this problem.

What about climategate—and other criticisms?

In 2007, a large batch of emails sent between scientists at the University of East Anglia were leaked to the public. The emails spanned more than a decade, and included plenty of rude language from the scientists—and also, according to critics, evidence that some of their data was fudged. Because this data was incorporated into the IPCC's fourth assessment report (AR4), some critics suggested the report could not be trusted.

Multiple investigations determined while some scientists had been insufficiently open with their data, the science in AR4 was sound. The report included other research; the process to compile these reports is intentionally rigorous, and does not depend on any single batch of studies.

Some journalists think a recent report may have included a sentence that will change the world.

There have been other controversies, too, including the so-called "hockey stick graph," which critics claimed overstated the case for climate change. On the other hand, some scientists worry that the IPCC often understates the extent of climate change, in part to keep politicians happy.

Ten years ago, there was a phase of particularly heated criticism. The IPCC was undergoing its first major reorganization after two decades in existence. Since, then, the agency has released a slew of reports—some of them quite urgent—without garnering major push back from the wider the scientific community. The science behind climate change is—like the IPCC's process—simply hard to refute. That means the reports, despite their dense science and wonky language, are sparking real change.

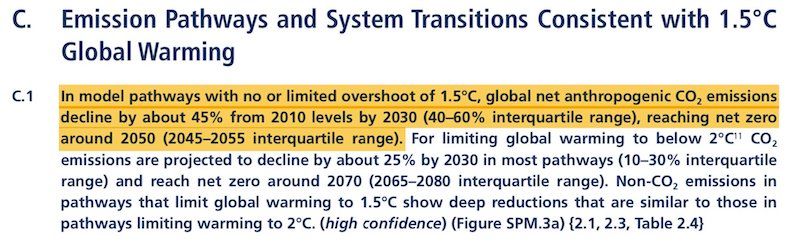

Bloomberg Green recently highlighted one sentence in particular. It's not a pretty one: "In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range)." This comes from a 2019 special report, and with its dull language relates a striking simple fact: if we want to keep warming under 1.5°C, we need hit net zero in the next 30 years—and see a sharp reduction in emissions by 2030.

One energy expert told Bloomberg that given the recent wave of government actions like the European Green Deal, this sentence may wind up being as important as the U.S. Declaration of Independence's "All men are created equal." Despite its bureuacratic drabness, in other words, the IPCC might just might be set to change the world.

Read this next:

Essential facts about pollution

November 4, 2020 · Climate knowledge