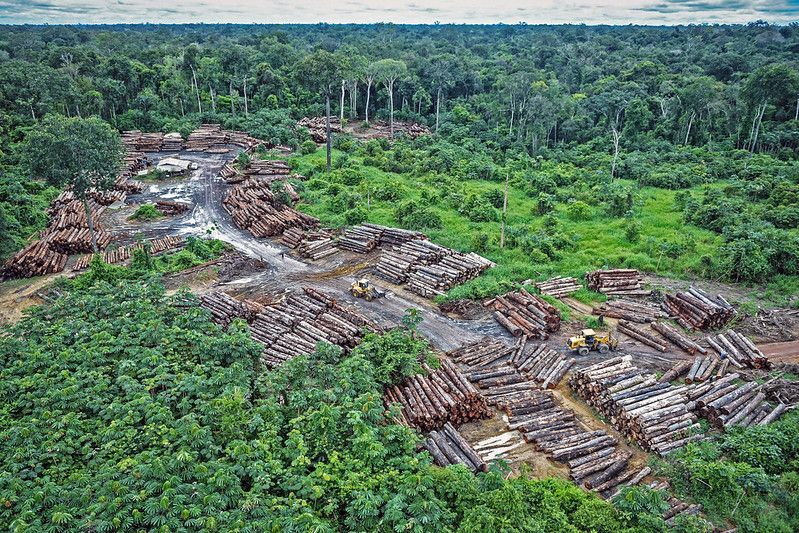

Trees are made of carbon. As much of half their weight is carbon, in fact, which is pulled from the atmosphere as the plants grow. This suggests a simple, essential strategy in our fight against climate change: More trees in the ground means less carbon in the sky.

Nonetheless, it can be incredibly tempting to chop down forests, especially in developing nations. With the trees gone, there is space to raise cattle or grow soybeans—to make enough money to leapfrog out of poverty.

The good news is that deforestation rates are slowing. The bad news: we're still losing trees far too quickly. Deforestation adds three billion tons of carbon to the atmosphere each year, which accounts for 10% of the world's emissions. That means that stopping deforestation should be a higher priority than planting new trees, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

What can we do? Here are some lessons from what's worked so far.

📚 Jump to section:

Pressure on industry

There was a time when Brazil was the third-largest source of global emissions, behind only the United States and China, due mostly to the its rapid rates of forest clearing. Then, for a period in the early 2000s, deforestation slowed. Some of this change can be attributed to "moratoria," or declarations by industry groups to stop sourcing products from deforested areas.

The most successful was the "soy moratorium": the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries and the National Association of Cereal Exporters both pledged to buy no soybeans that were grown on recently deforested Amazonian land. This move was prompted by public pressure, and in particular by a damning report published by Greenpeace in 2006.

Despite the moratorium, the Brazilian soy industry managed to thrive by increasing yields and harvesting the same land multiple times each year. Recently, though, there has been an uptick in Brazilian deforestation outside the Amazon, where attention is less stringent.

Better tech and data

Technology is key in the fight for forests. The Brazilian soy moratorium, for example, depended on satellite imagery for enforcement. But any single technology is imperfect: Lately, there has been a rise in small-scale clearing that is harder to see from satellites. Now innovators are looking for supplementary solutions. We can use acoustic recording to detect cutting. Groups have experimented with special materials that can be sprayed on trees, allowing illegal logging to be detected later in the supply chain.

From acoustic detection to dust-like sprays used to track the source of logs, technology can offer innovative strategies to decrease deforestation.

But more important than high-tech solutions may simply be more rigorous data. In 2005, the United Nations developed anti-deforestation program known as REDD+. (The acronym stands for a mouthful: "Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.") This is basically a framework that is supposed to offer guidance on effective approaches. Its existence has spurred hundreds of small projects across the globe fall. But results have been hard to assess, since it's difficult to know what might have happened had the projects not been implemented. To start replicating the most successful projects, we need to know what really is successful. This will require more rigorous research.

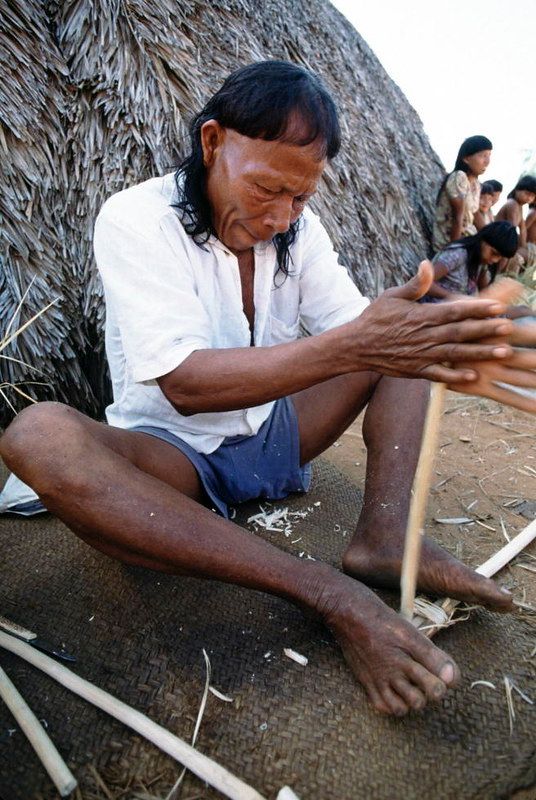

Empowering indigenous people

In Brazil, deforestation has recently jumped back up to match historic rates. One key culprit, according to many analysts, is a new president, Jair Bolsonaro, who has instituted industry-friendly policies and declined to enforce certain environmental laws.

Bolsonaro has been particularly aggressive towards the country's indigenous communities, vowing that no more land in Brazil would be declared indigenous territory. This is devastating for forests: deforestation is often lower on indigenous-held lands than even on state-protected forest areas. Rather than top-down dictates, this is a reminder that empowering indigenous communities manages to be effective and just at once. (One of the projects we support combines this solution with the previous, empowering an indigenous community providing better technology for tracking illegal incursions on their forests.)

Show forests the money

Here's an obvious axiom: more money solves more problems. Recognizing that forests provide valuable services and then paying communities for those services can make a substantial difference. Multiple studies have shown that such "payment for ecosystem services" programs tend to be popular in the communities they serve, too. Even simply paying for essential services for people who live near forest ecosystems can help: one study found that improved health care in a region near an Indonesian national park helped reduce illegal logging, in part because it reduced local economic stress.

We'll need to spend somewhere around $15 billion a year in order to hold deforestation down to the needed rates.

Whatever approach we take, though, we need more money. Across the world, we currently spend around $3 billion a year on REDD+ projects; most of this comes from just a few countries and institutions. To make the needed dent in climate change, this figure will have to jump to $15 billion or more, according to the Center for International Forestry Research.

What you can do

These solutions are complex, and often require action by whole governments or industries. So what is your role? There are a few small, simple steps to take, which are likely familiar: reduce, reuse, and recycle. The less wood and paper you buy, the fewer trees that need to be cut down. Working on a home project? Use reclaimed wood if you can find it. And when you can't recycle, look for a strong certification. (Greenpeace recommends seeking products bearing the FSC 100% label.)

There are bigger steps you might take, too. Cattle ranching is a prime driver of deforestation, so cutting back on beef matters. And a key solution, as always, is to get involved: give your time or money to groups that are fighting deforestation, and organize alongside others to make systemic change happen.

Read this next:

What is a carbon credit?

December 23, 2020 · Carbon Offsets 101