In 2004, after a hurricane barreled into the Alabama coastline, fishermen noticed that a certain pocket of ocean water yielded a good catch almost every time they visited. Eventually, a diver decided to head underwater to understand why.

He discovered the remains of an ancient forest that had been buried under mud and preserved. A series of intense hurricanes—likely caused by global warming—had churned the mud. Now, the forest was exposed for the first time in thousands of years. This discovery offered a scientific gold mine: there were underwater creatures we'd never seen before feeding off the preserved wood. Some of the genes scientists discovered may help us develop new medicines.

Climate change, in this case, helped us expand our knowledge of biodiversity. That's a rare upside. More often, climate change is killing off species—before we even know they're there.

📚 Jump to section:

What is biodiversity?

The word biodiversity is derived from the phrase "biological diversity." It was first coined in the mid-1980s, at the same time conservation biology was recognized as a scientific discipline. The intention was to create a word that might catch the attention of the public at large, and politicians in particular. Scientists wanted the public to understand the threats to life across the planet.

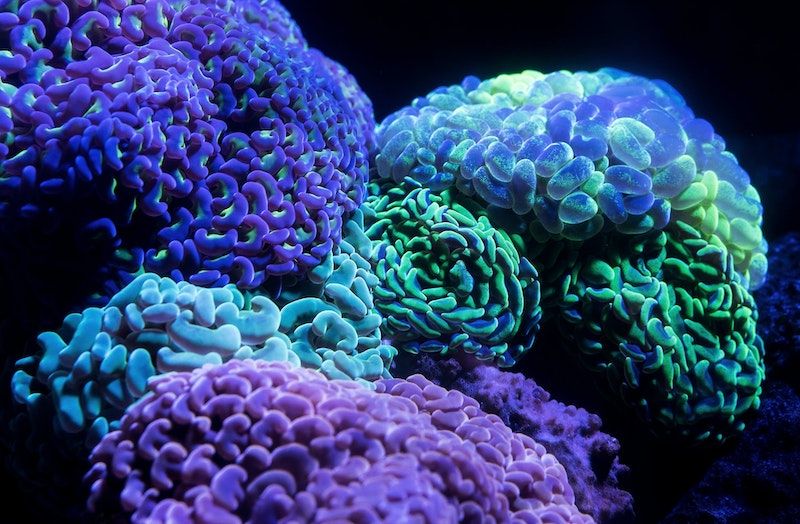

You can think of biodiversity as the incredible expanse of life across earth, though that is so broad as to become vague. The concept encompasses a few forms of diversity that are a bit more concrete. First, ecosystem diversity indicates the range of different habitats on earth, from coral reefs to rain forests to deep-sea volcanic vents—to ecosystems inside our own guts, even, home to countless bacteria. Next, there is species diversity, the range of species that exist, as well as diversity within each species; and, finally, there is genetic diversity—the massive library of DNA code that is scattered across the globe.

A recent estimate put the total global species count at 11 million—which is only a guess, of course. The same modeling suggested that around 86% of land-based species and 91% of ocean-based species have yet to be identified.

When it comes to DNA, the numbers are even more staggering—incomprehensible, really. There are 50 trillion trillion trillion DNA base pairs spread across the world. As the New York Times has reported, these together "would weigh 50 billion tons and fill one billion shipping containers."

That should put humans' small place place on the globe in perspective. Even by weight, we're barely anything at all: we make up 0.01% of global biomass.

What is happening to global biodiversity?

Scientists have calculated what is called the "background rate," the pace at which species go extinct without human intervention. A 2014 paper in Science suggested that the extinction rate is now 1,000 times higher than the background rate.

Despite being dwarfed by our biological peers, in other words, human beings pose a massive danger to the rest of life on earth.

Five times in world history, geological changes have resulted in mass extinction. Now, human beings are driving what scientists call the "sixth extinction." Academic journals are known for their dry and academic language. When it comes to this crisis, that is not the case: the decline in biodiversity has been called an "extinction tsunami" and a "biological annihilation."

In some ways, emphasizing extinction alone ignores the severity of the problem. The Living Planet Index looks at population counts across thousands of species. According to the index, the overall number of vertebrate animals on the planet has declined by 58% between 1970 and 2012. For invertebrate species, the numbers are worse: global insect populations have dropped by 75% over less than three decades. That means that even species that are not yet extinct (or even close to extinction) are plummeting in overall numbers. And a species doesn't have to disappear entirely for an entire ecosystem to collapse.

The biggest threat, at least for the species we know about, is direct overexploitation—too much hunting, fishing, and logging. But the expansion of human-dominated spaces, from farmland to cities, is a real problem, too; the second-biggest threat to species is habitat loss. Our globalized trade network also carries species far beyond their native range; sometimes, as they settle in new places, they thrive so well that they drive out other species. (For example, a few species of carp that were originally found only in Asia now make up more than 90% of the biomass in parts of the Mississippi River.) Biodiversity has been the focus of a ten-year effort by the United Nations, but a summary report released in 2020 indicated that none of the initiative's 20 goals were met.

One problem is how often we overlook this crisis. A recent analysis found that climate change generates eight times more news coverage than biodiversity loss. Really, though, the two need not be in competition: Climate change is already impacting 19% of the species that are listed as threatened or near-threatened. The same consumptive processes that drive global warming are prime drivers of biodiversity loss. As the globe warms, new pressures will arise, and in the coming years, the warming climate will be increasingly responsible for species loss—perhaps the primary driver in the Americas as soon as mid-century.

Why should this matter to me?

Sure, it's sad that plants and animals are disappearing. But if you're too cold hearted to simply preserve life for its own sake, it's important to know that plummeting biodiversity will hurt humanity, too.

The "services" provided by nonhuman life are nearly endless: bees pollinate our crops. Coastal wetlands soak up some of the force of hurricanes, protecting inland cities. They also, serve as carbon sinks—along with forests and grasslands and all kinds of intact ecosystems—pulling emissions from the air. A recent study, conducted by a Swiss insurance firm, found half the global GDP depends on such services.

Biodiversity matters for health, too. The coronavirus outbreak is directly tied to declining habitat diversity; as human land-use impinges on "wild" spaces, we find ourselves in more frequent contact with species we might otherwise never meet—and thus viruses pass from species to species. Being around nonhuman life also just just feels good; biodiverse spaces have been shown to improve psychological well being.

The underwater forest in Alabama was enticing for a different reason: it unveiled a new trove of genetics to explore. We are still discovering new genes that we can use, often in insects and bacteria: "Bioprospecting," as this is known, is used to produce fertilizers and medicines, perhaps one day even biosensors that detect pollutants.

Some researchers worry that bioprospecting—and other attempts to assign value to ecosystem services—may not be a viable conservation strategy; something only becomes valuable once it's very scarce. Still, it's clear that each species on earth contains valuable information: a particular way of surviving in this world. Each "has been hammered and shaped into its present form by mutations and natural selection," as famed biologist E.O. Wilson once wrote. Think of the world's genes as a library, showing all the ways to live. As species disappear, it's impossible for us to know just what essential stories we have lost.

Read this next:

What solutions can reduce deforestation?

October 19, 2020 · Climate knowledge