Sometimes the debate over climate change can feel like an ugly shouting match—just two sides with nowhere to agree. In the halls of power, especially in the United States, that may be true. But among the wider populace, there tends to be more nuanced positions.

Even in the U.S., where climate denial remains strong politically, the vast majority of people believe in human-caused climate change. So why does the debate persist, and what can we do about it?

📚 Jump to section:

Is there a scientific consensus that humans have caused climate change?

In a word, yes. The overwhelming majority of working scientists believe that human emission of CO2 has contributed to a warmer planet.

This is a result that has been confirmed in countless independent research projects. Scientists first began to explore the theoretical underpinnings of global warming in 1824. By the middle of the twentieth century, rising global temperatures and their cause became the subject of increasing scrutiny.

Recent reviews of the literature found that among currently publishing climate scientists, agreement that humans have caused climate change nears 100%.

Almost every major scientific agency and society has made a statement endorsing the science of global warming. (NASA has compiled a list of such statements.) In 2016, six different scientists reviewed the scientific literature and found that 90% to 100% of actively publishing climate scientists agree that the ongoing warming trend was almost certainly due to human activities. Think of human-caused climate change as a phenomenon that has been clearly discovered, much like gravity.

Even for scientists who may have questions about this theory, it's often incorrect to say they don't believe in global warming. There is a difference between denying climate change and remaining skeptical about elements of the current scientific model. A few scientists are "lukewarm" on certain aspects of the generally accepted theories. Almost none reject the idea outright.

Why is there still controversy, then?

Mitigating climate change will cost us money—and cost powerful corporations particularly. Some people, especially leaders within the oil and gas industry, believe that these costs are too high: that we should not sacrifice our economy for risks whose impact we cannot know with certitude.

Based on this hesitance, oil and gas companies haven taken steps to sow discord. They have funded campaigns intended to discredit the science and rewarded politicians who vote against climate policies. (The fact that internal scientists working for these companies have clearly understood the risks has led to lawsuits in the United States.)

These campaigns are ripe for success given that we live in what some observers call a "post-truth" world: Everyone is deemed suspect, assumed to be acting on their own narrow interests rather than pursuing the common good. Few institutions are universally trusted—scientists included. And because the media aims to provide "balanced" coverage, skeptics often receive space in papers and on TV far out of proportion to their actual numbers.

Take the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as an example. In 2010, the IPCC was accused of using bad science that overstated climate change. (At the same time, conflict-of-interest criticisms were being lobbed at its chairman; these were later investigated and dismissed by multiple independent parties.) At the same time, though, other groups of scientists worried that the IPCC was actually understating the extent of climate change, in part to keep politicians happy.

How big is the climate divide in the U.S.?

President Donald Trump has called climate change a "hoax," and the official Republican Party platform currently calls efforts to mitigate global warming "the triumph of extremism over common sense." Given such positions, climate-focused legislation has generally been a nonstarter in the U.S. Senate, where Republicans hold a majority.

The U.S., as a nation where climate denialism remains politically powerful, is something of a global outlier.

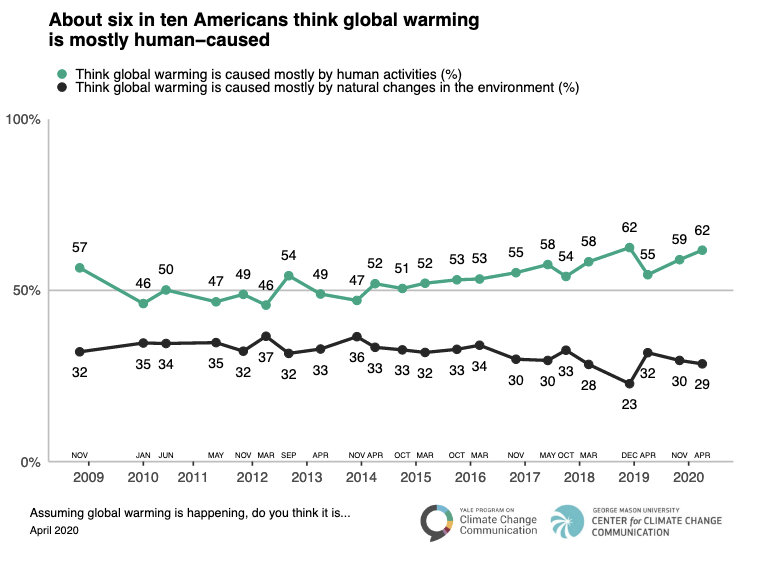

But this makes it easy to misperceive the extent of disagreement. Recent polling, conducted in April 2020, shows that 73% of Americans believe that climate change is happening—the highest number ever recorded. Only 10% of Americans do not believe in climate change. Further, the majority of Americans understand that climate change is human-caused. Within the Republican Party, there is an emerging split on the issue, as younger votes tend to be increasingly concerned about the climate. Other polls found that many people who understand climate change often overestimate the number of people who deny the science.

In the years to come, then, the bigger debates may focus on how to deal with a warming planet. Is geoengineering necessary, or is it too much of a risk? How much money should we invest, and how should it be invested? Is nuclear power an essential tool or an out-of-date technology? These are the questions we'll have to tackle. The science of climate change is settled; the policy is not.

Where is there room for compromise?

There are not just just two camps shouting at one another—or at least there doesn't have to be. As noted above, people tend to hold nuanced views, skeptical of some components of certain models, or worried about proposed solutions, while accepting nearly all the science.

Nonetheless, climate change "has come to serve as shorthand for which side you're on," as New York magazine put it in a recent article on the psychology of this issue. Social scientists have found that people with different political viewpoints tend to be spurred by different emotional motivators: self-described liberals tend to be worried more about harm to other people, while self-described conservatives are more frequently motivated by disgust.

How we frame the issue matters, in other words. For some people, it's about protecting the world; for others its about keeping the world clean. Certain kinds of personal stories—like the story of a sportsman emotionally processing climate change's impact on his favorite places to hunt and fish—have been shown to be effective across the political spectrum.

Lasting change in beliefs comes from deep engagement—not being lectured at, but having substantive conversations.

Lasting changes in our beliefs often come from deep engagement with issues. This does not necessarily require long discussions; studies have found people can come to a long-term change in as little as ten minutes. What changing one's mind does require, though, is making the connections for oneself: Rather than being given the hard sell on climate change, a person must take the time to consider how it fits in with their values and identity, including the future they want to see in the world. It's something to keep in mind the next time you find yourself on the verge of a debate: You're not likely to reason someone into submission with facts and data. All it may take is just a bit of space to reflect.

Read this next:

The many types of pollution

October 5, 2020 · Climate knowledge