A carbon offset is an effort to counterbalance some amount of carbon emissions, either by removing some carbon dioxide that's already in the atmosphere or by preventing future carbon emissions from ever reaching the atmosphere.

A carbon offset is almost always accompanied by a carbon credit—paperwork, basically, that certifies that someone, somewhere, has removed or avoided a tonne of carbon emissions.

This bit of paperwork opens all kinds of new possibilities—and also new kinds of trouble. In the final post in our series on carbon credits, let's take a dive into where carbon credits came from, and where they stand now.

Note: This is the third part in a series of carbon offsets. Read the first, an overview of common offset projects here; and the second, a look at what distinguishes high-quality offsets here.

📚 Jump to section:

From allowance to credit

The idea of offsets took off in the late 1990s, as politicians were crafting the first global climate-change treaty.

The Kyoto Protocol set strict limits on how many emissions each of the world's industrialized nations were allowed to release. The treaty included an emissions trading scheme, a system in which a regulator—the UN, in this case—issues "allowances," or paperwork that provides the legal right to pollute up to a specific limit. Each allowance generally corresponds to one tonne of carbon.

Offsets have been included in some legally enforced carbon-trading schemes as a way to allow flexibility. Increasingly, though, groups are voluntarily purchasing offsets.

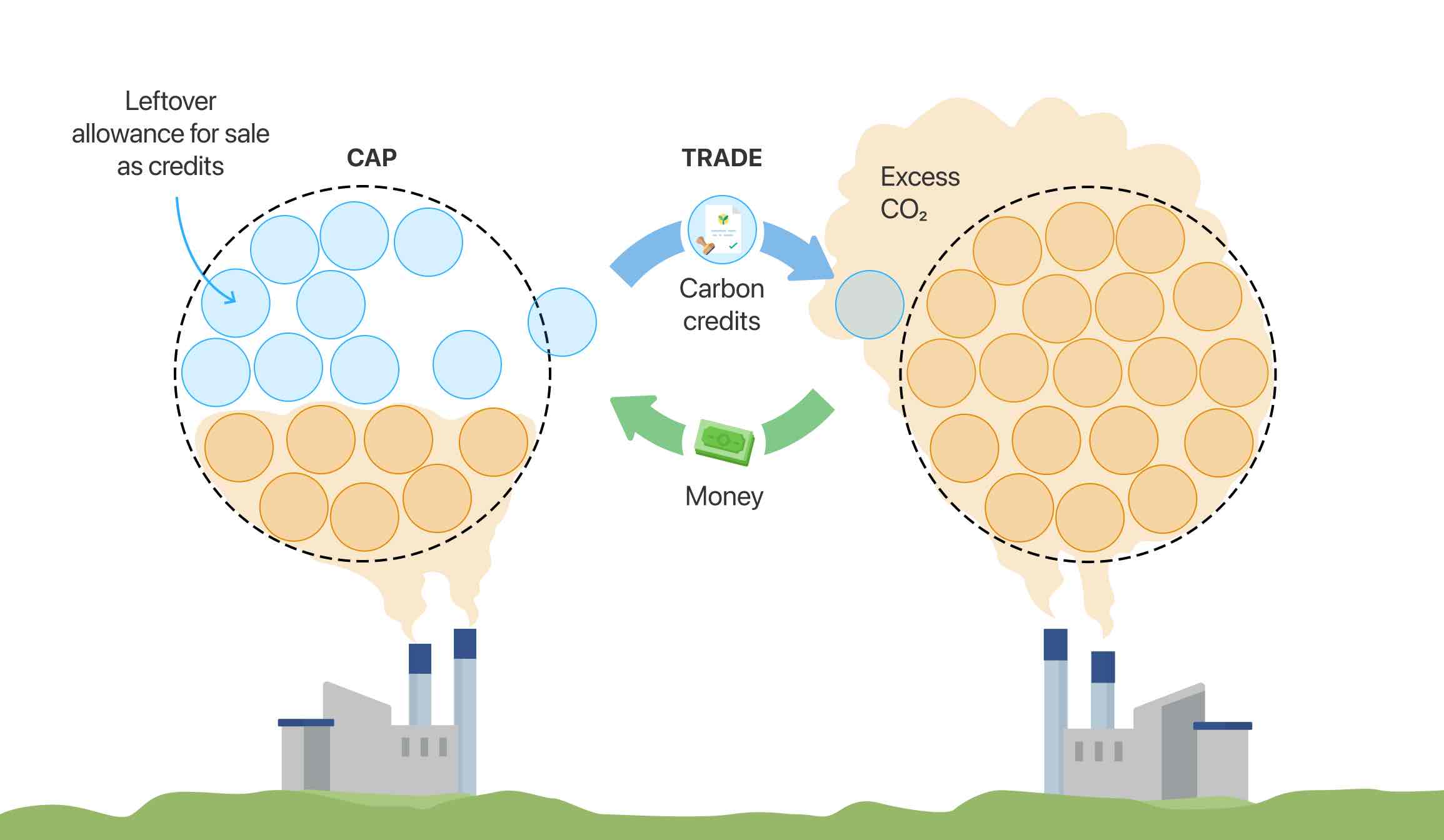

Participants in an emissions-trading system are allowed to sell their allowances. That means if one emitter—like the little factory on the left in the image below—finds it easy to get under its limit (or "cap," which is why trading systems are also known as "cap-and-trade schemes), it might sell that allowance to a emitter that's having a hard time.

In some places, you'll see the terms "allowance" and "credit" used interchangeably. I think it can be useful to distinguish the two, which is why I use allowance to refer to paperwork that permits emissions to be released. A credit, meanwhile, is paperwork that certifies carbon has been avoided or removed. An allowance can become a credit if it goes unused by its initial owner and is sold to someone else.

The rise of offset credits

It's worth noting that an emissions-trading system needn't necessarily allow for offset projects. The Kyoto Protocol could have set up a market for trading allowances alone, but a few countries, including the United States, lobbied for more flexibility. (Nevertheless, the U.S. never ratified the treaty.)

It's possible to build an emissions trading scheme that does not allow for offsets.

The treaty wound up including two flexibility programs, known as the Joint Initiative and the Clean Development Mechanism. These allowed countries to invest in projects outside of their borders and take credit for the resulting reduction in emissions. They could even invest in projects in non-industrialized countries—which were not otherwise bound by the Protocol! The idea—at least in part—was that since this is a global problem, it mattered less where emissions were reduced than that they were reduced. Thus, offsetting was born.

It was an imperfect system. Germany, for example, decided that rather than reducing its emissions completely it would invest in a number of projects to help India wean itself off coal. Later, though, researchers found that Indian developers considered this payment "cream on the top." They were already going to build these projects—renewable electricity, as noted in my last post, just makes economic sense—and now they got even more money. So, despite Germany claiming an offset, the amount of emissions in the world did not go down.

Who issues credits?

According to the World Ban, the Clean Development Mechanism has been responsible for more than half the carbon credits ever issued. 2019, though, marked a change.

In the U.S., most companies have no legal prompt to pursue offset projects: the country never joined the Kyoto Protocol. Increasingly, though, many have decided they want to be carbon neutral. Some hope to improve their reputation with consumers. Others may have realized that their longevity depends on a stable climate, and have decided to act accordingly.

This has helped prompt the rise of what's called "voluntary" carbon credit markets—as opposed to "compliance" systems like the Clean Development Mechanism.

If companies are earnestly working to mitigate climate change, they need to be sure the projects they support are legitimate and effective. Multiple organizations have arisen to help ensure this: carbon creditors vet the offset projects to ensure they meet standards; then they will issue carbon credits; and, once those credits are purchased, they will record that fact. This is called "retiring" credits, and is meant to ensure no project is double-claimed.

Prominent examples carbon crediting agencies include Climate Action Reserve, the American Climate Registry, the Gold Standard, and the Verified Climate Standard—the last of which sold more credits than anyone else this year, including any government-backed compliance systems.

The early failures of the UN's offset programs offered plenty of lessons for these organizations. Still, in our opinion, no one has completely cracked the nut of large-scale carbon credit registries yet. Some problematic offset projects are just bound to slip through the cracks. (For example, the American Climate Registry has been criticized recently for certifying forest projects as offsets even though the trees have already been protected for decades.)

Ensuring carbon offset projects are legitimate requires rigorous research and follow up.

Wren is slightly different than these large registries. We aim to connect individual consumers to projects that remove or avoid carbon emissions. Most individuals don't need an official "credit"—you're probably not trying to prove to shareholders that you've reduced your carbon footprint, after all! So we do not issue official "credits." That said, we work hard to be even more rigorous than any of the major carbon offset registries, and are very selective about which projects we work with. We have scoured the globe to find a small handful of projects that we think are delivering real results, and only choose projects that can back up their work with rigorous data, and that are willing to provide regular updates.

Read this next:

A simple guide to the Paris Agreement

October 20, 2020 · Climate knowledge